How Phillis Wheatley Might Have Obtained the Approval of Eighteen Prominent White Men of Boston to Publish Her Book of Poetry

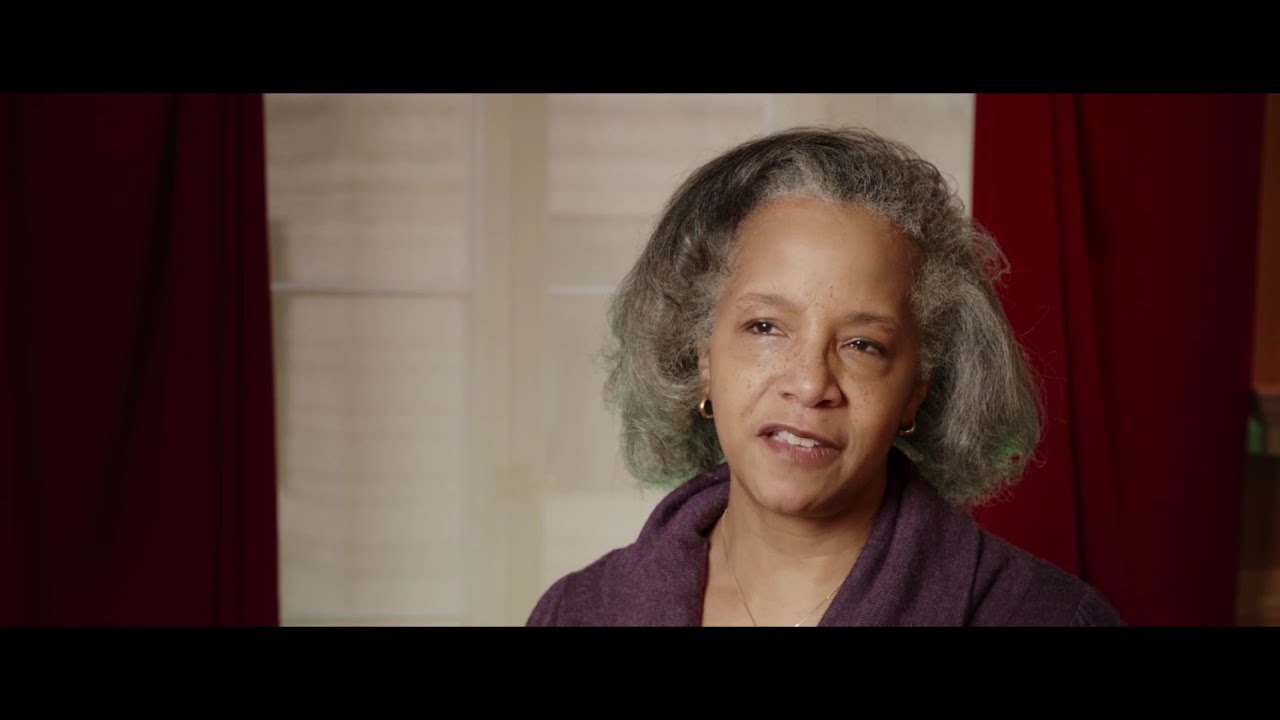

As Phillis Wheatley sought to publish her first book, there were many who doubted that an enslaved Black woman was capable of such an accomplishment. It has been suggested that she was questioned in person by some of Boston’s most prominent men; it is undoubtedly true that her book contains a statement from prominent town leaders vouching for her work. Jeffers here imagines the courage it likely took 20-year-old Wheatley to face down their judgment and manage the balancing act of intellect and subservience that was likely required to secure their approval. This poem was filmed in the Council Chamber at the Old State House, where two of the men who signed the statement — Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lt. Governor Andrew Oliver — would have met with members of the Massachusetts legislature.

In Context | Primary Sources | In Phillis’s Words | Further Reading

In Context

In September 1773, a London-based advertisement for Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects featured an October 1772 “attestation,” a document signed by 18 “up-standing” gentlemen from the American colonies confirming that these poems were indeed written by a young African woman who was enslaved in Boston.

The attestation has fueled speculation in some quarters that Wheatley was subjected to an in-person, all-male inquisition. However, more recent scholarship theorizes that her poems indeed may have undergone a reading examination by “the best Judges who think them worth of the Publick View'' in February 1772 as part of a publication proposal to secure subscribers, but it is unlikely Phillis Wheatley herself was interrogated.

It is also likely that this attestation was a publisher’s marketing tool that connected the poet and her intellect to some of the most learned men in New England at the time. Historians have pointed out, however, that many names on the attestation are of those that are related by blood or marriage to the Wheatleys. Phillis Wheatley herself never wrote specifically addressing the attestation.

Primary Sources

Links to documents and artifacts relating to the moment and events referenced in the poem.

Library of Congress, The Boston Censor dated February 29, 1772

This periodical provides judgement on Phillis Wheatley’s work. Though not currently digitized, however, it is available through the Library of Congress’s Microform Reader Services here.

Massachusetts Historical Society, Phillis Wheatley’s Writing Desk, dated 1760

This is the desk where Phillis would have penned the same poems that were questioned and examined by these eighteen white men.

In Phillis’s Words

Excerpts of Phillis Wheatley Peters’s writings that resonate thematically with Jeffers’s poems.

“...Imagination! Who can sing thy force?

Or who describe the swiftness of thy course?...

...But I reluctantly leave the pleasing views,

Which Fancy dresses to delight the Muse;

Winter austere forbids me to aspire,

And northern tempests damp the rising fire;

They chill the tides of Fancy’s flowing sea,

Cease then, my song, cease the unequal lay.”

Further Reading

Links to additional resources.

- The Age of Phillis by Honoreé Fanonne Jeffers

- The Endorsement of Phillis Wheatley by J.L. Bell

View the Films