Imagining the Age of Phillis

The Visionary Poetry of Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

For many, Phillis Wheatley Peters is well known as a poet, but not as a woman. She is mainly remembered as a literary prodigy and enslaved girl in 18th century Boston who became the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry.

Poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers sought to revive and expand our collective memory of Phillis through her award-winning book The Age of Phillis. Jeffers’s evocative work calls on us to imagine Phillis through her other identities: a daughter of Africa, a friend, a wife, a mother, and an author who spoke to the historical moment of the American Revolution.

Revolutionary Spaces commissioned a short film series called Imagining the Age of Phillis to bring a selection of the poems from Jeffers’s book to life. Directed by John Oluwole ADEkoje and produced by Patrick Gabridge of Plays in Place, the series was filmed on location in Boston at our two sites — Old South Meeting House, where Phillis was a member of the congregation, and the Old State House, down the road from the Wheatley family home.

We hope Jeffers’s work and these films inspire you to dig deeper into the history. With each short film, we’ve included a variety of resources that offer opportunities to expand your understanding of Phillis Wheatley Peters and the time in which she lived.

View the Films | Timeline of the Life of Phillis Wheatley Peters | About the Artists

View the Films

A Brief Timeline of the Life of Phillis Wheatley Peters

The poems in Honorée Fanonne Jeffers's The Age of Phillis explore the world of 18th-century Boston through the lens of Phillis Wheatley Peters's identity and experiences. We offer here some brief historical context to better understand her short, yet impactful life.

On July 11, 1761, a young enslaved girl, aged around 7 or 8, landed in Boston after a grueling journey from West Africa. Sickly and frail, she was named Phillis for the schooner that brought her to North America, and given the last name Wheatley, for the family that purchased her. John Wheatley, a prominent merchant, and Susanna Wheatley, his wife, lived on busy King Street at the heart of Boston’s social, economic, and political life. It was in the Wheatley home that this child prodigy honed her literary skills, fed by the intellectual activity at the center of town and by deep connections with religion and the church.

Phillis Wheatley composed her first known writings at the young age of about 12, and throughout 1765-1773, she continued to craft lyrical letters, eulogies, and poems on religion, colonial politics, and the classics that were published in colonial newspapers and shared in drawing rooms around Boston. In 1772, she sought to publish her first book of collected poems. At the time, authors were often the driving force in the publication of their work, and had to secure financial commitments from a group of individual subscribers to convince a publisher to print the work. Despite multiple advertisements in the Boston Censor in early 1772, she was not able to reach the 300 subscriber threshold needed to get the book into print.

Susanna and Phillis Wheatley then turned their attention overseas. Phillis Wheatley traveled to London to visit various English elites from June to July 1773, accompanied by Nathaniel, Susanna and John Wheatley’s son. While they intended to meet Phillis Wheatley’s publishing patroness, Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, the two would unfortunately never connect; Wheatley left London toward the end of July 1773, purportedly due to Susanna Wheatley’s failing health.

Still, the trip likely reaped some rewards for Wheatley. Throughout 1773-1774, copies of Phillis Wheatley’s poems were published in newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic, and a London-based publisher printed her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in the fall of 1773, officially making her the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry.

By October 1773, Phillis Wheatley was back in Boston, where she was now a free woman waiting ardently for copies of her books to arrive. “Since my return to America, my Master has at the desire of my friends in England given me my freedom,” she writes to Colonel David Wooster. In an odd coincidence, her books arrived in December 1773 on the Dartmouth, one of the ships involved in the Boston Tea Party.

In early 1774, Susanna Wheatley passed. Phillis Wheatley continued to work in the Wheatley household until 1778, when John Wheatley and his daughter Mary both died. In November 1778, she married John Peters, a free Black man. Information about Peters is woefully fragmented. Like many at the time, the couple experienced consistent financial hardship in the wake of the post-Revolutionary War economic depression. Records show that John Peters was in debt and Phillis failed to secure subscribers for a second book of poetry in both 1779 and 1784. It is speculated that the couple had children, all of whom predeceased them.

Wheatley Peters passed away due to unknown causes at the end of 1784. An obituary from December of that year reads: “Phillis Peters formerly Phillis Wheatley aged 31, known to the literary world by her celebrated miscellaneous poems. Her funeral is to be this afternoon…” The manuscript for her second volume of poems was lost and never published. Though Phillis was buried in an unmarked grave, the location of which is lost to history, her words and legacy are forever remembered and interpreted by scholars and writers.

About the Artists

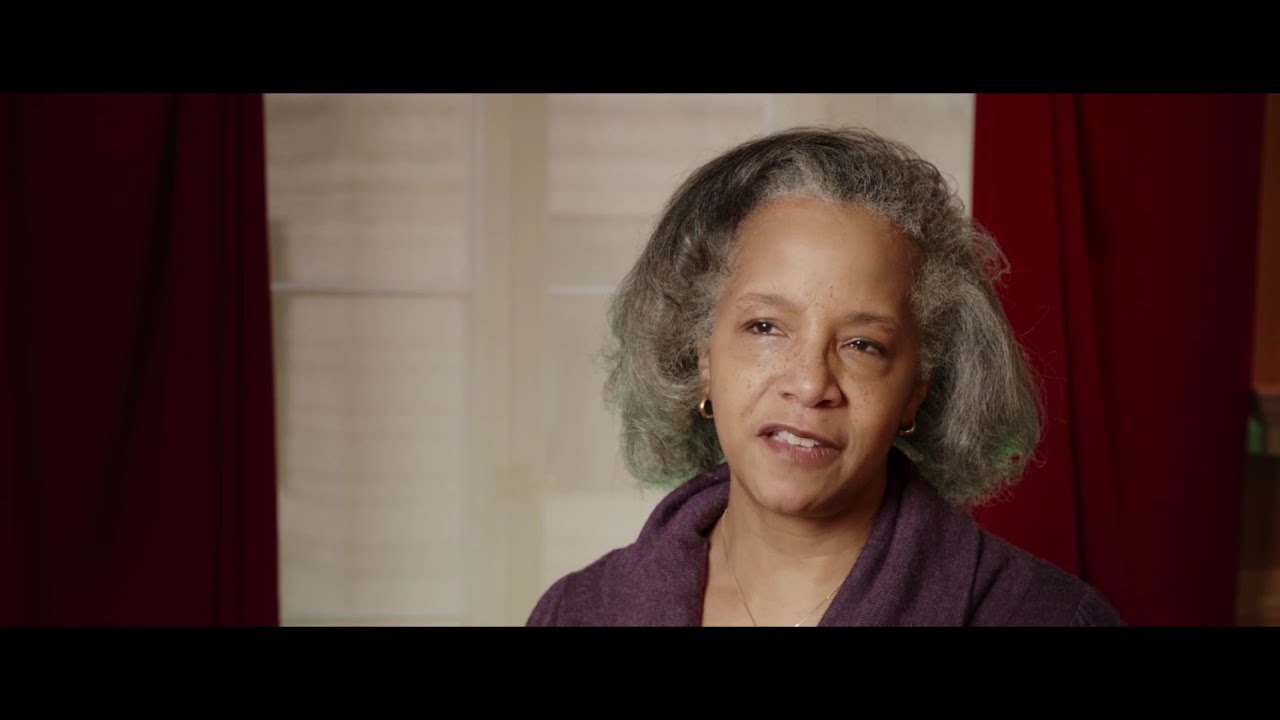

HONORÉE FANONNE JEFFERS (Poet) is the author of five poetry books, including The Age of Phillis (Wesleyan 2020), long-listed for the 2020 National Book Award and winner of the 2021 NAACP Image Award in Poetry. In addition, Jeffers has authored one forthcoming novel, The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois (Harper 2021). She has received fellowships from the American Antiquarian Society, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Witter Bynner Foundation through the Library of Congress. Currently, she is the 2021 USA Mellon Fellow in Writing. Jeffers is Professor of English at University of Oklahoma.

JOHN OLUWOLE ADEKOJE (Director) is a national award winner of The Kennedy Center's ACTF Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award for the play Street Hawker; as well as a recipient of The Roxbury International Film Festival's Emerging Local Filmmaker Award for the documentary Street Soldiers, which also showed at the Pan African Film Festival in Cannes, France, The World Film Festival-Montreal, and the BronzeLens Film Festival in Atlanta. ADEkoje has received the Brother Thomas Fellowship Award and he is a playwriting Fellow at the Huntington Theater Company. Most recently, he was awarded the Emerging Filmmaker Award for Knockaround Kids, his narrative feature, at the Roxbury International Film Festival which all showed at the Urbanworld Film Festival in New York. Knockaround Kids can be found on Tubi, Amazon prime, Google Play, Apple and other film platforms. ADEkoje is the co-director and director of photography for the digital version of Hype Man (Company One/American Repertory Theatre) as well as the writer, director and projection/art designer for the Triggered Life Project (Portland Playhouse). He teaches film production and theatre at Boston Arts Academy.

TAILINH AGOYO (Voice in "Boston Massacre") is co-founder and director of We Are the Seeds of Culture Trust, a non-profit organization committed to uplifting and amplifying Indigenous voices through the arts. Tailinh has worked as an actor in film and television for over 30 years. She is a proud mom to four beautiful children.

Still, the trip likely reaped some rewards for Wheatley. Throughout 1773-1774, copies of Phillis Wheatley’s poems were published in newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic, and a London-based publisher printed her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in the fall of 1773, officially making her the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry.

BRANDON G. GREEN (Man) is Boston-based artist and educator from Selma, AL. Recent stage credits: Sweat (Chris) with Huntington Theatre Company, Black Odyssey: Boston (Ulysses) with Front Porch Arts Collective, and Nat Turner In Jerusalem (Nat) with Actors Shakespeare Project. Recipient of the Elliot Norton Award for Best Actor for Company One/Arts Emerson's production of An Octoroon and Best Ensemble for Black Odyssey Boston and Sweat. Voice Over: "The Ordinary Epic" as Marcus/Benedict; "The 54th in '22" as Greg. The product of a village of educators, Brandon has proudly taught at various high schools and universities throughout the Boston area. All love to Actor 6. Alabama State University - BA. Brandeis University - MFA. ILYLG.

MARC PIERRE (John Peters / Male Voice in Approval) Most recent credits include Emmy and Absolution (Skeleton Rep), Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (Huntington Theatre Company), Three Musketeers (Greater Boston Stage Company), Cardboard Piano (New Repertory Theatre), Fences (Florida Repertory Theatre), Gloria (Gamm Theatre), Brawler (Kitchen Theatre Company), Airness (Actors Theatre of Louisville), Milk Like Sugar (Huntington Theatre Company), When January Feels Like Summer (Central Square Theater), Peter and the Starcatcher (Lyric Stage Company), and The Flick (Gloucester Stage). Television and film credits include "Castle Rock" (Hulu) and Twelve (Radar Pictures). Mr. Pierre is a recipient of the Isabel Sanford Scholarship and holds a BFA from Emerson College.

CHERYL D. SINGLETON (Elizabeth Freeman / Female Voice in Approval) is very pleased to be working again with Plays in Place, having previously appeared in The America Plays at Mount Auburn Cemetery. Cheryl is a professional actress and arts leader with stage, screen, television and voice-over experience. Some of her credits include performances with: Front Porch Arts; Theatre On Fire; Lyric Stage Co.; New Repertory Theatre; Wheelock Family Theater; Gloucester Stage; Boston Playwright’s Theater; Commonwealth Shakespeare; American Repertory Theatre & Zeitgeist Stage; as well as productions with Ryan Landry and The Gold Dust Orphans, Queer Soup and ImprovBoston. A proud member of Actors’ Equity and StageSource, Cheryl serves on three arts boards in the Boston community.

SABRINA VICTOR (Phillis Wheatley Peters) currently reigns as Miss Massachusetts USA 2020. She is an artist of many fields - actor, arts activist, model, content creator, social media influencer, and speaker. Theater credits include: The Donkey Show (American Repertory Theatre), School Girls, Or; The African Mean Girls Play (SpeakEasy Stage), and Miss You Like Hell(Company One). Sabrina graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with two undergraduate degrees in Theater and Journalism, a Multicultural Theater Certificate, and Commonwealth Honors. www.sabrinakvictor.com

REGINE VITAL (Obour Tanner) is an actor, dramaturg, director, writer, educator, scholar, and storyteller from Somerville, MA. She has worked with several Boston area theatre companies, including ArtsEmerson, Company One, Central Square Theatre, HUB Theatre Company, Fresh Ink Theatre, and Flat Earth Theatre. Regine holds degrees from Boston University, UMass Boston, and recently studied Shakespeare at King’s College, London and Shakespeare’s Globe. She has taught composition and introductory literature at the college level; text and performance to high schoolers; and continuing adult education classes in literature. Currently, Regine is Manager of Curriculum and Instruction at the Huntington Theatre Company.

PATRICK GABRIDGE (Producer) is a playwright, novelist, and screenwriter whose work has been read and produced around the world. With his company Plays in Place he creates new site-specific plays in partnership with museums and historic sites, including Mount Auburn Cemetery, Boston’s Old State House, Old South Meeting House, and Roosevelt-Campobello International Park.