Transforming Representatives Hall

At the end of 2019, as we geared up to change exhibits in Representatives Hall in the Old State House, we noticed a fair amount of cosmetic updates that needed to be made. We thought we were in for some paint touch-ups, minor plaster work, and a good cleaning. Once our preservation team took a closer look, we realized the issues we set out to fix were not superficial by any means, and extended beyond skin-deep.

Our Facilities and Preservation Manager, David Rodrigues, helps explain what made these changes more difficult than we first thought.

Much like how humans naively made use of toxic products once thought to be harmless like lead-based products and asbestos, there are also materials and techniques that have been used in many historic sites over the years that are actually harmful to their health.

Much like how humans naively made use of toxic products once thought to be harmless like lead-based products and asbestos, there are also materials and techniques that have been used in many historic sites over the years that are actually harmful to their health.

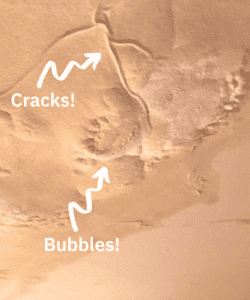

The Old State House is no different. As we looked at cracked walls and bubbling paint, we realized that the building was being slowly suffocated by “newer” building techniques and materials from decades ago. Different layers of the building were in conflict with each other: The oldest elements work together as an organic system that flexes with changing environmental conditions, but newer materials – such as paint and common drywall – blocked the natural healing properties of the building’s organic elements.

How does this conflict result in building damage? Let’s start with the fabric of the building.

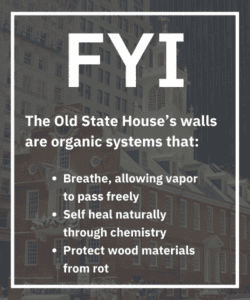

The layers of the building are made with lime that has the ability to flex with temperature and humidity changes in the building. Using lime is a building technique originally developed by the Romans and widely used until the 1840s.

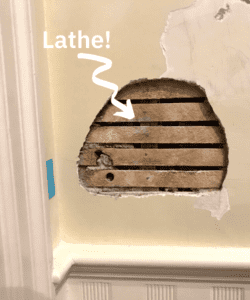

Builders originally applied the plaster on top of brick or “lathe,” which is a series of small wood strips. When plaster is pushed through lathe, it creates a bulge that holds the plaster wall firmly to the lathe. When plaster is applied directly to brick walls, the lime in the plaster and the lime in the brick create a tight bond to secure the plaster wall firmly to the brick.

Builders originally applied the plaster on top of brick or “lathe,” which is a series of small wood strips. When plaster is pushed through lathe, it creates a bulge that holds the plaster wall firmly to the lathe. When plaster is applied directly to brick walls, the lime in the plaster and the lime in the brick create a tight bond to secure the plaster wall firmly to the brick.

In either case, the lime easily flexes and repairs itself as needed.

Where did we go wrong?

As humans demanded greater control over indoor environments, construction techniques evolved to completely encapsulate the building envelope. New products like interior oil paints introduced in the 19th century, and latex paints in the 20th century, created surfaces that were impermeable to moisture. This means the organic walls of the historic building could no longer breathe and repair naturally.

Over time, with nowhere else to go, pockets of moisture and air built up in the layers of the building, creating bubbling and cracks visible on the interior walls of Representatives Hall.

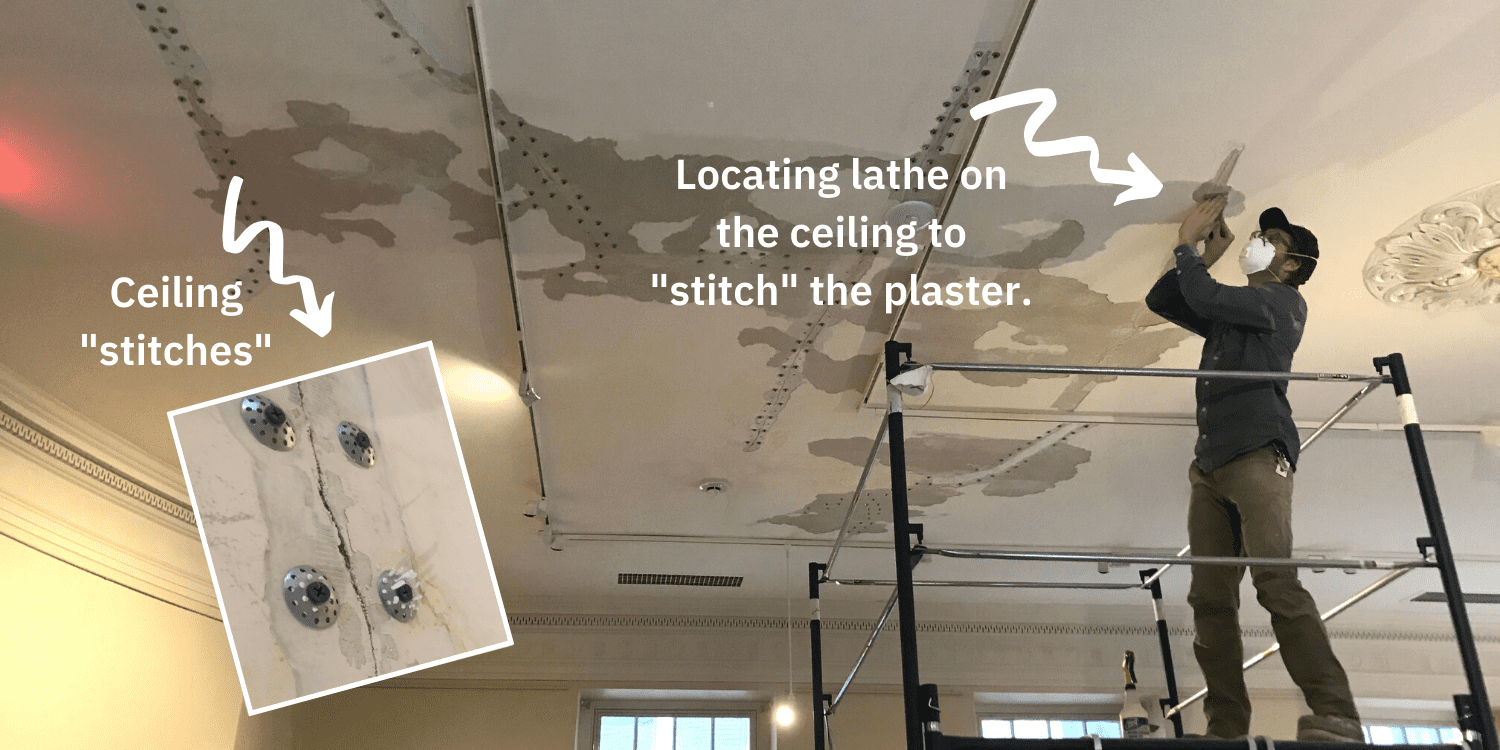

Surgery! As small cracks were not allowed to heal, they developed into large cracks that came detached from the bones of the building – the lathe – and the trapped moisture within the walls created soft pockets that had to be dug out and repaired like a cancer. To repair these “cancerous” pockets, we had to tap on every square inch of the walls and ceiling and listen for subtle changes in the tone. Once we identified where the voids were, we were able to remove and replace the damaged plaster.

But the ceiling involved even more work.

Over the years, large chunks of ceiling plaster became separated from the lathe. Previous repairs were done using modern “drywall” techniques to stitch the chunks back together. However, the plaster was never actually re-attached to the lathe, so the damage was masked, but not repaired. With these techniques, the ceiling was doomed to repeatedly fail and crack in the same places over and over until massive chunks of plaster would eventually fall to the ground. By re-attaching the plaster to the lathe along the cracks and repairing the cracks with Lime plaster and “stitches”, the cracks will eventually heal themselves naturally.

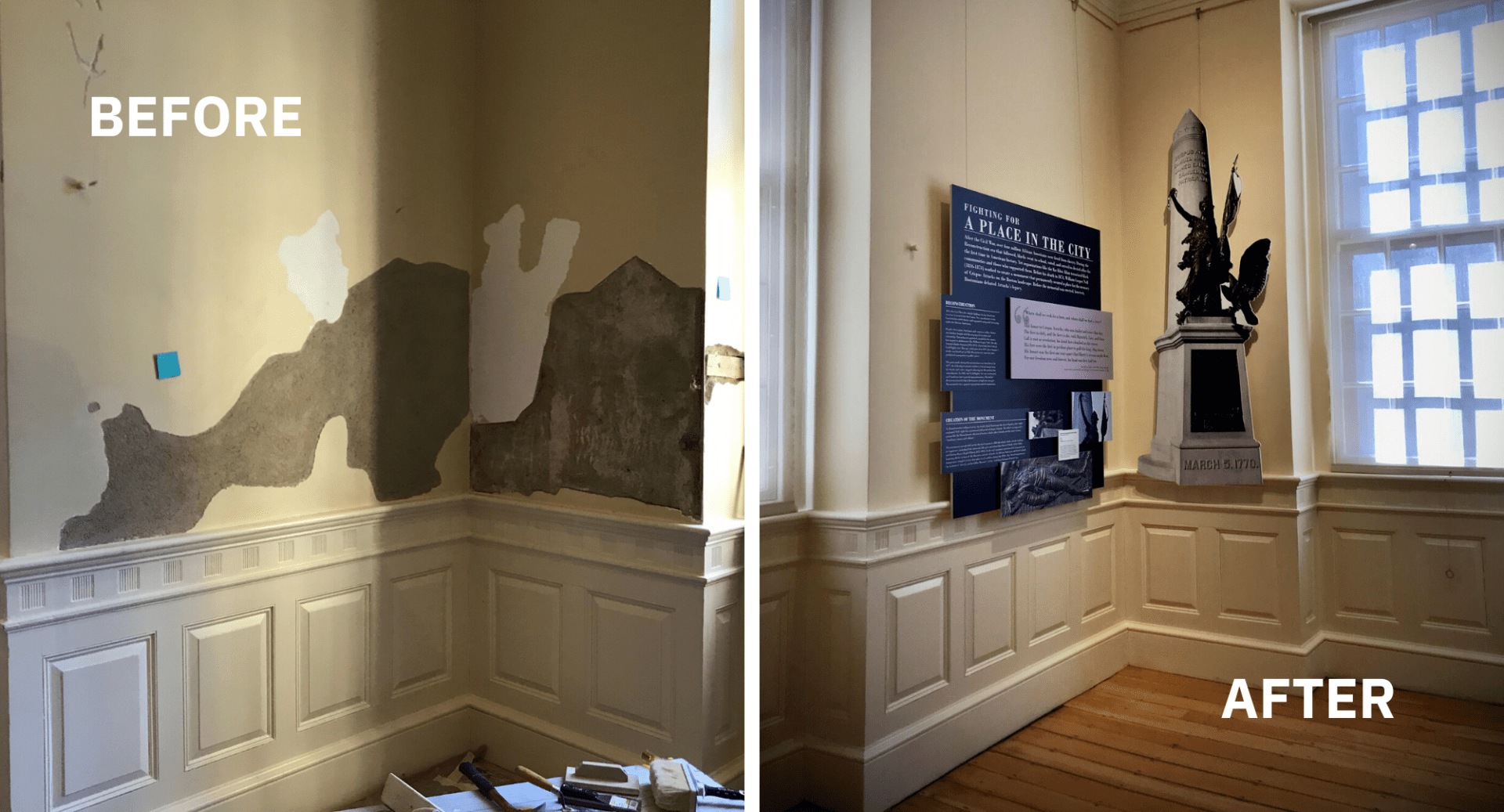

After fixing the plaster using the technique described above, and applying a layer of new breathable paint, we were able to fully repair the cracks and bubbles in the walls and ceiling of Representatives Hall.

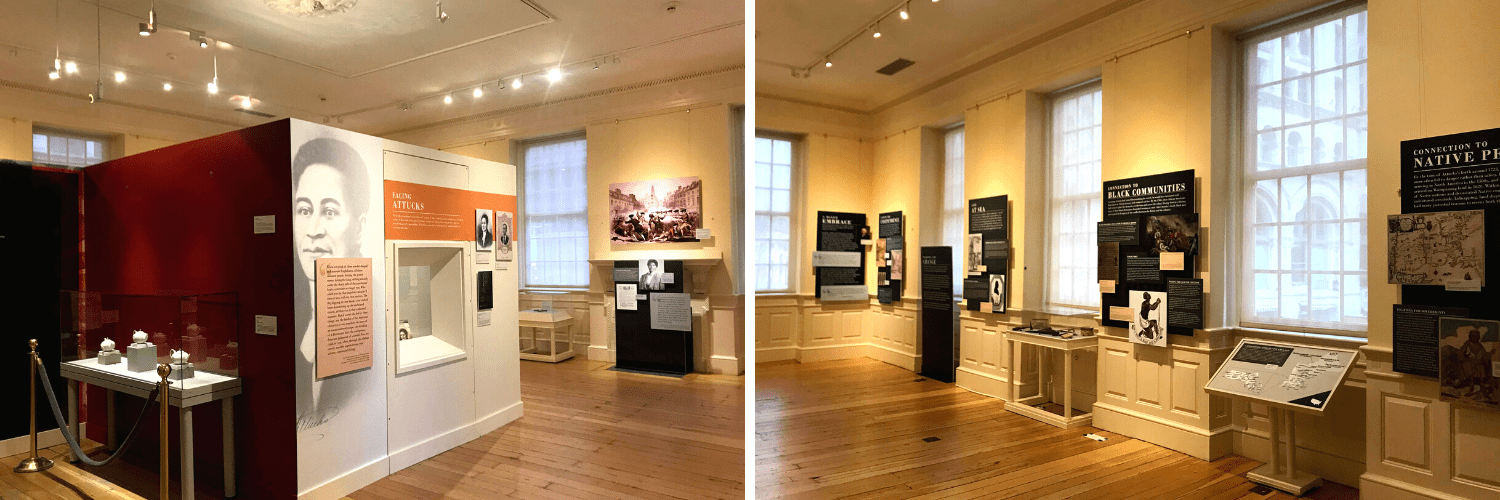

With all said and done, we were thrilled to stay on track to open our Reflecting Attucks exhibit on March 5. And even though we only got to see the exhibit in person for just over a week before closing due to COVID-19, we can’t wait for the day when we can safely peruse Representatives Hall once again.

What other building elements are you curious about at the Old State House or Old South Meeting House?