Life at Sea

Crispus Attucks was most likely a sailor or a dockworker. At the time, two-thirds of people in colonial America’s maritime industry were of either African or Native descent. On the docks in Boston Harbor, Attucks likely encountered many discontented sailors and colonists of all ethnicities who opposed British authority and the presence of “redcoats” in the town. He also would have been aware that the ships he sailed on were part of a network that supported the slave trade.

A sailor’s life in the 18th century was not easy, but many chose it as a way to escape poverty, enslavement, or indenture. On these ships, racially diverse crews worked together and travelled across empires and oceans. They were men of the world. Attucks was described as being based in the Bahamas and ready to sail for North Carolina at the time of the Massacre.

However, the maritime world was full of contradictions. While ships created freedom for some people, they also transported African and Native people who were enslaved. Ships carried disease as well as food for enslaved people in the Caribbean. While African and Native sailors and seamen from Boston found opportunity on the seas, they may have experienced moral conflict.

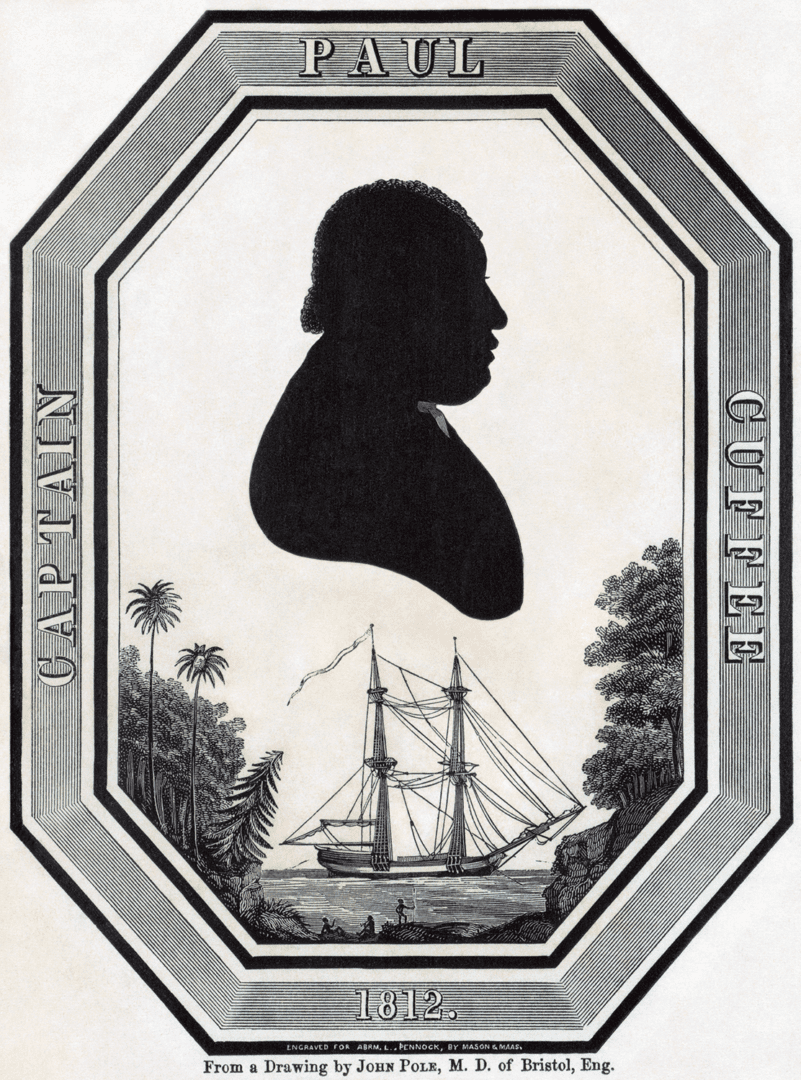

PORTRAIT OF CAPTAIN PAUL CUFFEE

From a drawing by John Pole, M.D.; Engraved for Abrm. L. Pennock by Mason & Maas.

1812

Engraving

Reproduction

Click image to view larger.

A successful sailor, merchant, and abolitionist, Paul Cuffee (1759-1817) was an extraordinary example of the possibilities of life at sea. Born to Ruth Moses, a Wampanoag, and Kofi Slocum, a freed African, Cuffee became a whaler in 1773 and then a ship’s captain. By the end of his life, Cuffee had developed a lucrative shipping business, supported abolition in Boston and Philadelphia, and funded African American settlement in Sierra Leone.

By the time Crispus Attucks took to the seas, conflict between sailors and British military officials was well known. Sailors often protested against British authority and fought openly with British soldiers. John Adams (1735-1826) noted that “between [sailors] and soldiers, there is such an antipathy, that they fight as naturally when they meet, as the elephant and rhinoceros.”

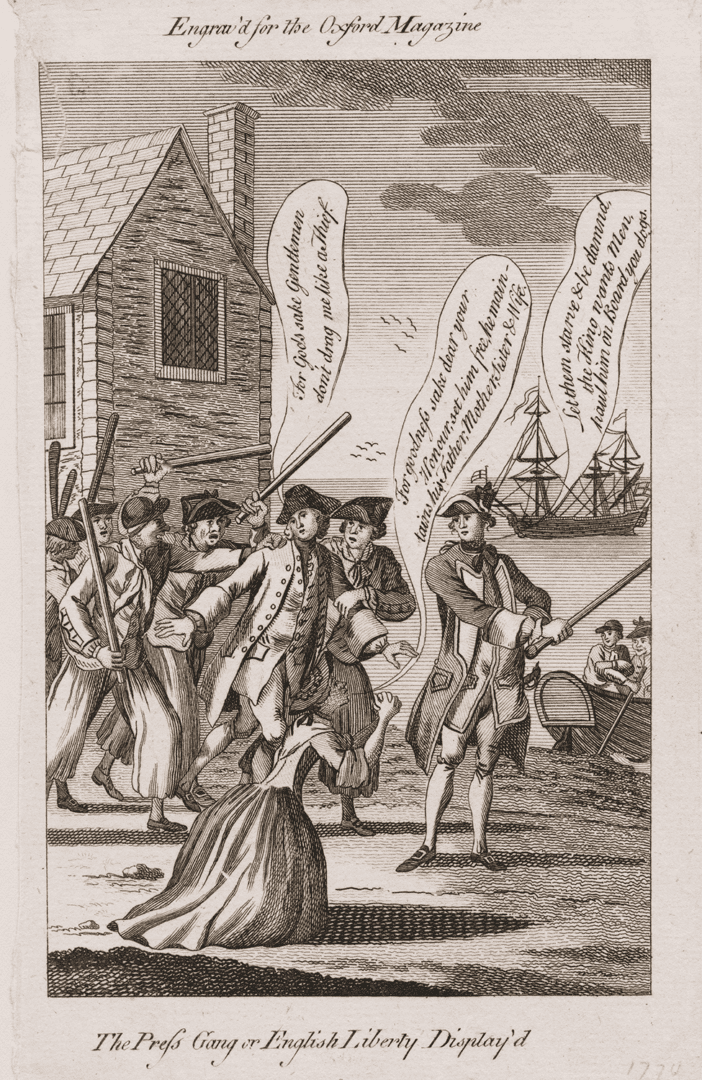

A particular source of conflict was the British Navy’s practice of impressment, which involved forcing sailors into military service without their consent. Sailors used to freedom on the high seas rebelled at the idea of submitting to military discipline. In 1747, when Attucks was in his 20s and possibly beginning his life as a sailor, Admiral Charles Knowles ordered the impressment of Boston sailors and workers. In response, hundreds of residents caused a three-day riot that crippled the colonial government. Protesters forced their way into the Old State House, broke windows, and stormed the governor’s Council Chamber.

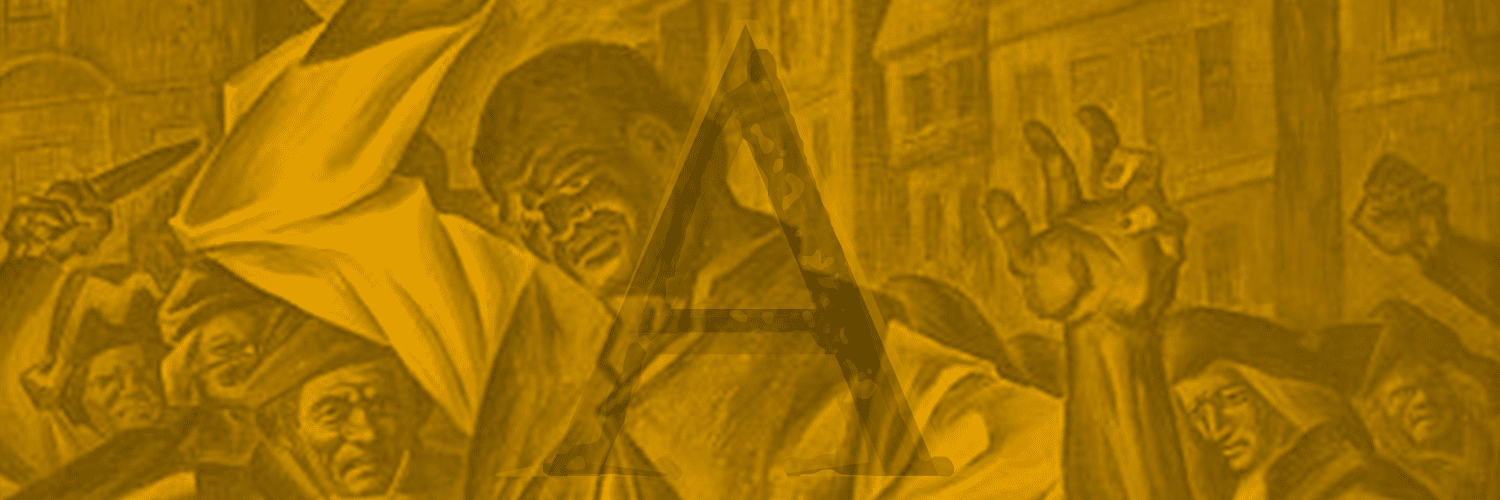

THE PRESS GANG, OR, ENGLISH LIBERTY DISPLAY’D

Artist Unknown

1770

Etching

Reproduction courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Click image to view larger.